Photography: Courtesy of Showtime

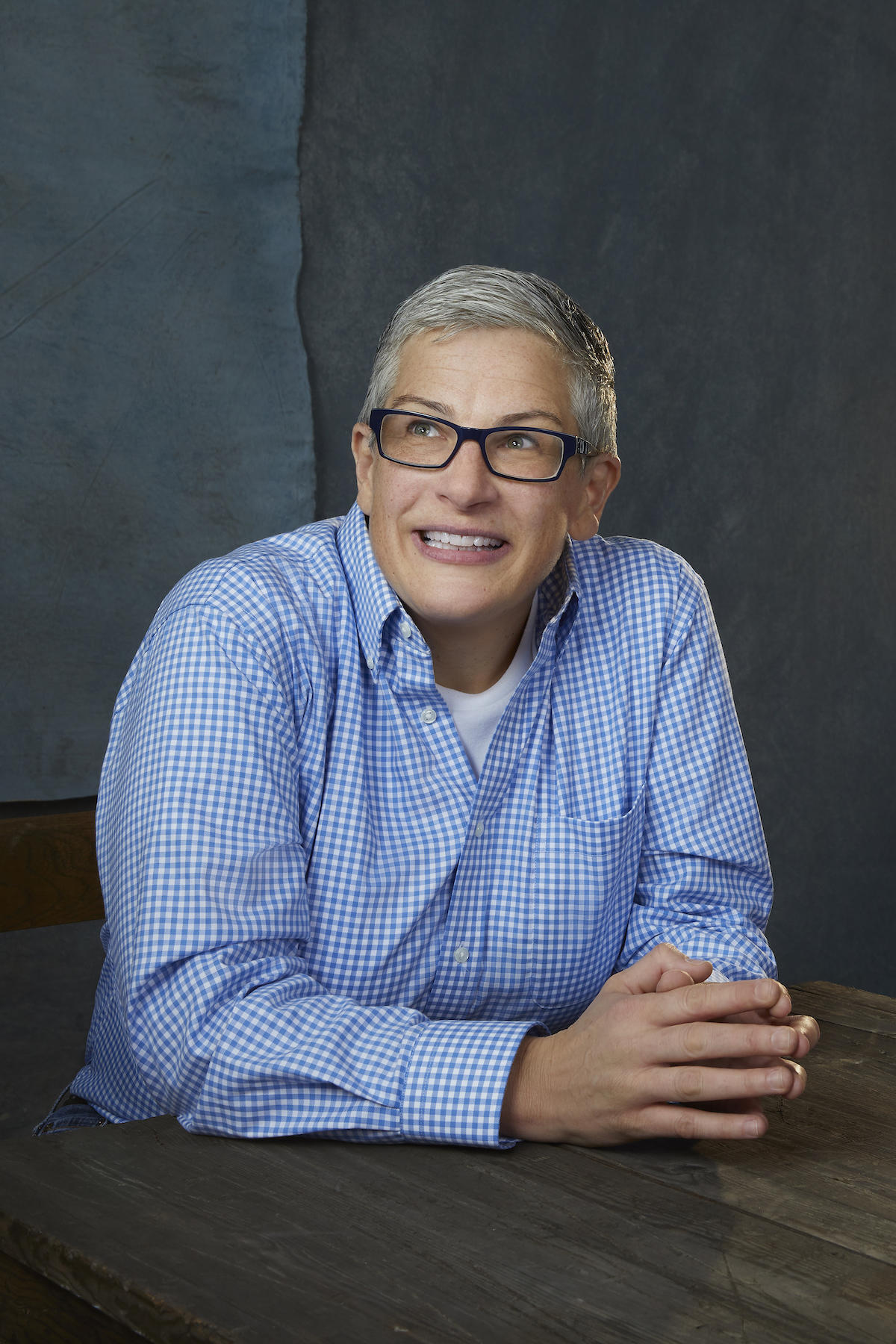

Photography: Courtesy of Showtime Abby McEnany is single-handedly changing the landscape of representation. By landing her first TV deal at the age of 51 for her seminal series Work in Progress, McEnany has brought a new narrative to Showtime – one that is equally as intelligent and sensitive as it is extraordinarily funny. The series, which explores cross-generational queer life and relationships through the lens of an older “fat, queer dyke” has radicalized the TV-scape as we know it today, bringing with it a much necessary and heartfelt new account to the forefront. Our publisher and founder, Kristin Prim, caught up with Abby to talk about the pitfalls of rejection, mental health, and the absolute triumph that has become Work in Progress.

KP: First of all, I just want to start by saying what a genuine joy it is to have a show like Work in Progress on the air. Like many others, I watched it for the first time right after The L Word on Showtime, and I actually ended up stopping all of the work that I was catching up on that night just to see it in full. As a person myself, I don’t find much on TV or even in film funny, but it honestly was one of the most incredible, heartwarming, genuine, and funny shows that I have ever seen. I’m pretty sure that I fully annoyed all of my neighbors just by laughing hysterically at 10:00 PM every Sunday.

I watched a clip that you did with Showtime though, where you said that it getting picked up kind of came as a surprise, as you were initially just thrilled to have it get into Sundance. What was it like to experience that? It must’ve been so exciting, and in many ways, also incredibly validating. That’s such an exciting thing.

AM: Yeah. First of all, I’ve got to say, thank you so much. It means the world to me, and I don’t want that to sound glib or trite, but really thank you very much. I think this comes a lot from having OCD and having that magical thinking where if you say something is happening that jinxes it, so when all this was happening I was like, “Yeah, I just don’t believe it,” because it was too amazing to be true. I’m still in this state of utter… like… what’s happened over the last 18 months? It’s immense gratitude, and just a realization that no one person ever does it by themselves.

So, our co-EP’s said, “We’re pretty sure that Showtime’s going to say yes, and they’re going to want you to go quickly. We don’t have a deal yet, but you should start writing.” We started to write without a contract – and we were going to meet the Showtime execs – but that got delayed. When we finally met Gary and Dave – Gary Levine and Dave Binegar – it was so great. We actually had met Dave at Sundance, he’s just an amazing person, and Gary has been amazing as well. But, I was still like, “Oh, so it’s signed?” And our people were like, “No, it’s not signed.” Because this is all new to me… uh, what does that even mean? But once it did get signed I was like, “Oh! That’s good!” But it didn’t seem real. Then they released the trailer and I thought “Huh, I mean it looks like a TV show.” But I didn’t fully believe it until it premiered on December 8th. You know what I mean? I’m just that person.

KP: I believe that! It must be such a surreal experience.

AM: It really is. I’ve been in the Chicago improv community for so long, and know of so many people who have had those “it was so close” moments, so I was very aware that it could go away at any moment. It’s just how I am.

KP: That’s a good way to be.

AM: Yeah. I met these hilarious and innovative people at Sundance and they had an inked deal with a network for their show, but it was taken away at the last minute. And shit like that happens all the time, so I’ve just tried to be very aware of how fortunate we are.

KP: Yeah, it’s so exciting.

AM: Yeah, and I have such a wonderful family, bio and chosen. They were just like, “Oh my gosh, you did it!” But I was still saying, “I don’t know, don’t jinx it.” I had hardly told anybody anything. I told 10 people, “Don’t tell anybody, but we have a meeting. Don’t tell anybody, but it looks like it’s a go. Don’t tell anybody!”

KP: [Laughs]. I’m exactly the same way, so I understand. The show is semi-autobiographical, and it touches on many personal issues from OCD to depression, which I find to be so incredibly important and also very timely, especially for where we are right now. Was there any anxiety or hesitation on your part just in terms of how raw it is?

AM: No, I think my anxiety and hesitation come from how much of myself I was going to share. It’s so funny, I always say… well I don’t know if it’s funny, but this actually came out of a solo show that I did in 2016 called Work in Progress. It was very personal, but in my intro, there are like 60 people [in the audience], and I’d be like, “Okay, everything I say in here stays in here.” I wanted some sense of control over these personal stories. I’m not on social media, I consider myself a private person, and then I share all this shit. I think once the reality hit me that the character I play in the show is named Abby McEnany, that’s where my anxiety is.

But am I anxious about talking about mental illness? No, I’m not. I just think the fact that there’s so much shame and stigma about it is so harmful. It’s been harmful to me, and it’s been harmful to so many people I know and love. You just read about it and hear about these kids and stuff, I don’t know. When people hide that stuff, I understand it, it’s only people’s business to share if they want, but I don’t want to be one of those people that’s ashamed of it. It’s a hard enough life that we live and I can throw out my own shame about mental illness… it’s just a pain in the ass to live with.

It’s just fucking hard, but hiding mental illness is exhausting. I don’t know if that answered your question. I would say that my anxiety came more out of opening myself up. Some of the scenes were very difficult to shoot, like the washing hands scenes – I was not in a good place. It was a very private thing, and you have to do it over and over again. Those were not good days because that’s not a fun thing for anybody with OCD. Somebody once said, “You love to wash your hands.” I’m like, “I hate to wash my hands! I hate it!”

KP: Yeah, I understand! Something else that I absolutely love about Work in Progress is, for lack of a better way of putting this, confronting the seemingly sometimes-overwhelming generation gap within queer culture. People in their teens and 20s are now growing up with so many more terms and labels to identify with that mostly didn’t exist 20 years ago.

AM: Yes!

KP: Is any of it based on lived experiences or was it more of a metaphorical thing than anything else?

AM: It wasn’t really apples to apples, but yeah, it was definitely based on real stuff. I look at it with such love and wonder regarding how it is for younger queers now. When I came out, my community was very cis and white. And again, now if you live in a city, it’s not that way – it’s like every gender expression, every sexuality expression, all different races, all different religions, all different abilities. The openness is just so beautiful, and it’s overwhelming. There’s a scene that I always call “Queer Wonderland” where Chris takes me to this queer party and I’m just in wide-eyed wonderment. There’re fat performers that are being lauded for their beauty, their sexuality, and their artistry, and I’m just like, what is happening? A lot of this is breaking down those barriers. I look at it in absolute wonder and appreciation. I have so much to learn, and I’m always learning, and I fuck up all the time.

KP: Me too.

AM: Yeah, and I just want to set up this world where it’s okay. If you fuck up, then you learn, and let’s create a world where we don’t immediately vilify somebody.

KP: Right! I’m pretty young, I’m 26, but there’s still so much that I am still even confused about and try to learn. I totally understand, and it is overwhelming at times to be honest, but it’s so interesting and beautiful and fascinating at the same time. But even me, sometimes I’m still like, “Okay, wait. Break that down for me?”

AM: Right, and I think that’s okay. It’s so funny because I love the opening up of identity. It used to be that either you were gay, lesbian, or bisexual, and that never felt quite right. At first, I was bi, then I came out as a lesbian, but I was still into some guys. For some reason bi never fit with me, and please – I am pro-bisexuality, and God bless, because there is a lot of anti-bisexual bullshit out there and I’m not one of those people. Once I came across the term fluid, I was like, “Oh, fluid? That makes so much sense to me.” I think that it’s wonderful and to have questions is okay, and also it changes, it keeps on evolving, and I think that’s just such a beautiful thing.

KP: Yeah, absolutely. I agree on all of that. One of our incredible editors, Alexandra Julienne, and I, we recently spoke to Lea DeLaria and she named checked you as one of the –

AM: No way!

KP: Yes way! She named you as one of the individuals who is leading the charge in terms of queer representation in entertainment today.

AM: What!?

KP: Yes!

AM: I met Lea DeLaria once. Oh my God, I’m losing it.

KP: I actually just read through that interview and we were talking about how, especially today, even age groups are becoming more diverse.

AM: Okay, I’m sorry. I’m having a little moment. Okay, okay.

KP: She’s amazing. Were there any female or queer comedians or entertainers that you looked up to while you were growing up? Or, if not, who did you admire when you were younger?

AM: I’m 52, so in the 1970s as a kid there were no queer comics that I’m aware of… well, that were out, anyway.

KP: Lea said Julia Child.

AM: [Laughs]. Oh my God, that’s seriously hilarious. I was a huge fan of Steve Martin’s records, and then of Gilda Radner, and also Jane Curtin. Those were the people that I loved, and then also Richard Pryor. As a kid I’d see Richard Pryor (and Gene Wilder) in movies like Stir Crazy. I wasn’t listening to his standup at that time, but those comedians were who I gravitated to as a kid.

KP: You told The Guardian that establishing a show like Work in Progress was always a goal in a sense, especially since, “There are not a lot of women like [you] in film or on TV.” Something that is still, of course, very true. Representation is gratefully increasing, but it’s still not at the levels that it should be. What advice would you offer to women who struggle with not seeing themselves depicted in the ways that they should?

AM: Orange Is the New Black is an example of a show that was so groundbreaking in representation. It was so groundbreaking; age, size –

“I feel so lucky that I have this bonkers opportunity now, that I got it at 51, and I know who I am, and I know what's important to me, and I know what I will not compromise on, and I know what's worthwhile to me.”

KP: I genuinely think it’s been one of the most culturally prolific shows.

AM: It is, yeah. I’m always like, “I could see myself as an extra on Orange.” I wouldn’t stick out, you know what I mean? Okay, so advice. I’ve got to say, to add to the fact that there weren’t tons of roles for me, I’m also a horrible auditioner, so even if I got two auditions a year for random-ass commercials, I never got a call back. I was bad at auditions. So: write your stories, tell your truths. The only reason that this happened, that there’s a show with somebody like me on it, is because I wrote it.

To add to the fortune, I also had my partner – who came to my [one-person] show – be like, “Hey, do you want to write a show?” I was like, “Yes.” And again, when Lilly Wachowski came on board, who’s been a friend of mine for a long time, it was incredible. I’m very fortunate, lucky, and grateful.

KP: That’s an incredible team to have.

AM: It is incredible. I’m just so lucky. If you don’t see yourself, nobody is going to do it for you. You’ve got to do it for yourself. Start creating that. Know who you are, and then write that. And then also collaborate and work with people that you love and trust.

I was 51 when I was on my first professional set, when I got my first gig. I never had a gig before. I mean, I’ve done some a bunch of improv and sketch, but I had never booked anything. It might take a while, but it also might not. I think that my advice is to create the work that you want to see because if you’re waiting to see yourself, you might not.

“I think that my advice is to create the work that you want to see because if you're waiting to see yourself, you might not.”

KP: I really love that. And that actually leads into my next question. I read in the same piece that it was your – and again, I’m quoting you – “abysmal” history of auditioning for roles that spurred you to write for yourself. In the same way, I was really forced to pave my own path after having multiple doors slammed in my face, which has actually become something that I’m so incredibly grateful for, because it allowed me to build this incredible career that I never would have had otherwise. What advice would you lend to women who struggle with those aspects of rejection?

AM: Oh, gosh. I don’t know if I have an answer to that. One of my sisters is a psychologist… I called her after a horrible addition where the auditioner was so terrible and yelling at me (and then about me to the waiting room), and she was like, “I just find it interesting that this is the career that you chose.” The whole thing is rejection, people talking about you behind your back, never knowing what people are thinking… it is horrendous. I don’t know.

This is the only thing that I ever wanted to do though, and I’m here in Chicago where I get to be a part of this amazing improv community. Therapy works a lot for me. I’ve had very bad times. I don’t know the answer. You should surround yourself with people that you trust and that can give you real talk.

You know, when people are like, “Oh, that was amazing!” And you’re like, “That was the shittiest show that I’ve ever done!” Actually, one of my best friends, Nancy, she’s always like, “Oh, you were the best one up there!” And I’m like, “It was a solo show, Nance.”

KP: [Laughs]. That’s amazing.

AM: But it can be brutal, and I still am haunted by some of the stuff. You’ve just got to keep getting up and doing it if you really want to do it.

KP: Yeah, I can’t imagine doing that. When I was younger I modeled for a hot second, and I wouldn’t do it again with any regularity. It’s just not something that… I don’t know… I feel like the act of performing is just not my thing. I give you guys so much credit, and even models, bless you all.

AM: Yeah. It’s just being utterly ripped apart, and every little thing is wrong.

KP: It takes a tremendous amount of strength, passion, and all that stuff. I don’t know if I have that in the performative sense.

AM: Yeah, you choose what you want to be passionate about. I don’t know. That’s so hard. I can’t imagine how difficult that was.

KP: It’s not the life for me, but it is for some people and that’s great. What do you think the single most important thing that you’ve learned throughout your career has been? If you have something.

AM: Okay. It’s funny, when we get off this I’m going to be like, “Okay, that wasn’t the single most important thing.” It’s a caveat, this definitely comes with a caveat. It goes back to “know who you are.” I came to stuff pretty late in life, and that’s not being self-deprecating. I had my first real girlfriend at 29. It took me 6 years to get through college. I auditioned for the Second City National Touring Company over a period of 10 years, and then I finally got it. I feel so lucky that I have this bonkers opportunity now, that I got it at 51, and I know who I am, and I know what’s important to me, and I know what I will not compromise on, and I know what’s worthwhile to me. A part of me is like, this might be taken away and that would be so bad, but I’ve known failure before.

KP: It’s very freeing.

AM: Right, and I’d rather feel confident in the choices that I’m making on an ethical/moral/heart/brain level. I feel fortunate that this came later in life. I know what’s important now. I guess just know yourself, know what you want, and what’s the most important, and know what you will not compromise on.

KP: I love that. That’s a good one.

AM: Oh, good. Thank God.

KP: [Laughs]. For many of our interviews, I like to leave off with the question that we try to examine daily here at The Provocateur. What do you think makes a provocative woman?

AM: As I have to Google what provocative means…

KP: [Laughs].

AM: I would say that a provocative human being is somebody who is honest, living in their truth, and refusing to take compromises in their own life. This is really hard. It’s so funny because if you say provocative woman, I think that that can have very many different meanings. The way that it historically has been used…

KP: I would say now – well, currently I always say – that to me a provocative woman is a woman who is kind. We’re living in a world full of such cruelty that I think it is extremely provocative and very rousing to be kind, to be compassionate. That’s always my answer to it. Though if you were to ask that 20 years ago, I’d probably say it was a woman showing her tits or something.

AM: Right, that’s so funny because that’s definitely how it has been meant in a social way. Yeah. I would say somebody who is honest, wants better things for people, and won’t be quiet about it.

KP: That’s a great answer. I really love that.